Here’s Lady Susanna Hamilton, Countess of Cassillis, 1632 -1694. First wife of the 7th Duke of Cassillis. I recognised the name. As with every portrait, unless it's the Queen or somebody, you say to yourself, "Who is this?" so I leant forward to read the label beside the painting. Cassillis? Oh... There had been a pub called the Cassillis near where I grew up. Charlie McGill was a regular. There's also scandal involved. The title of Cassillis has something to do with the Marquess of Ailsa and there was, in the 1970s, a young Countess of Ailsa or Cassillis or something who had more than a passing interest in the milkman. Then there's the Ballad of Johnny Faa and the Earl of Cassillis' Lady and, no doubt, an extended web of cultural association, history and experience that made me stop at this painting.

Lady Susanna, as represented in the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, is an entirely separate self. She is safely fenced off from the other selves in the gallery by a stout wooden fence known as a "frame". They all have them. They've all been framed. The place is full of them. Individuals all. Lone horsemen. Sir Walter Scott. Bonnie Prince Charlie. Flora McDonald. Kirsty Wark. It is not impossible to imagine a National Portrait Gallery with one exhibit: a great big fresco, to include all the notables, freely interacting with each other. If one goes out of favour, no problem, scrape them off and paint on a new one. But that's not what we've got. That's not how we see ourselves. That's not how selves were seen in 1667 when this portrait was painted. No man is an island? Well, all of these ones are. Often under protective glass, the individuals represented are sealed off from each other. Lady Susannah is single, but not ready to mingle. You can look but you can't touch.

Frames are clearly important. Some of them are elaborately carved or moulded, there's often a lot of gold leaf. They focus the I. This bit. No. This bit here. Look at this. Here. Not over there. This is the important part, here, within this carefully delineated perimeter. There's an almost funereal quality to some of these big frames, all that gold gives the impression of an ornate coffin, open, with the dearly departed resting, open-eyed, for eternity. Unless, of course, it is a portrait of Schrodinger’s cat. When the gallery is closed, how do we know if the cat’s eyes are still open? (No emails from physics graduates or references to fridge doors please. I’m a busy man.) Framing has come to mean a way of understanding. To understand the individual we need to separate it from its peers, to isolate it and look at its unique qualities, those aspects that define it as a discrete individual:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

Robert Burns - To a Louse.

Aye, Rab, fine, but suppose we didnae? Suppose I stick a wee "not" in there. What if we don't see ourselves as others see us?

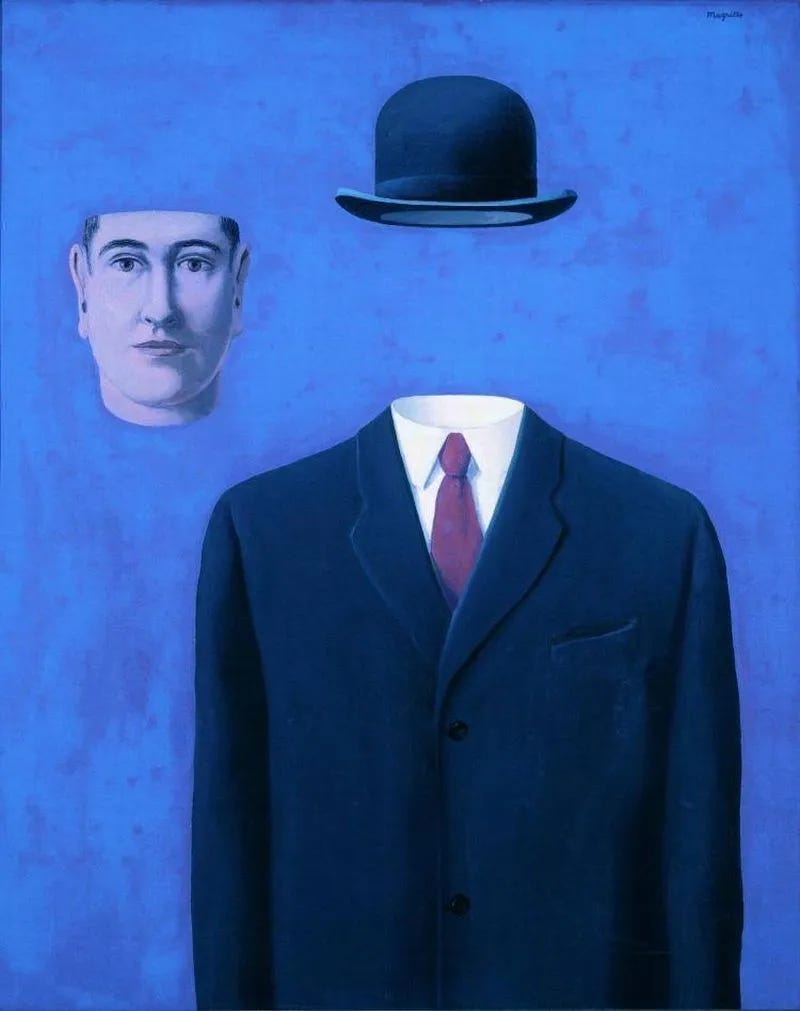

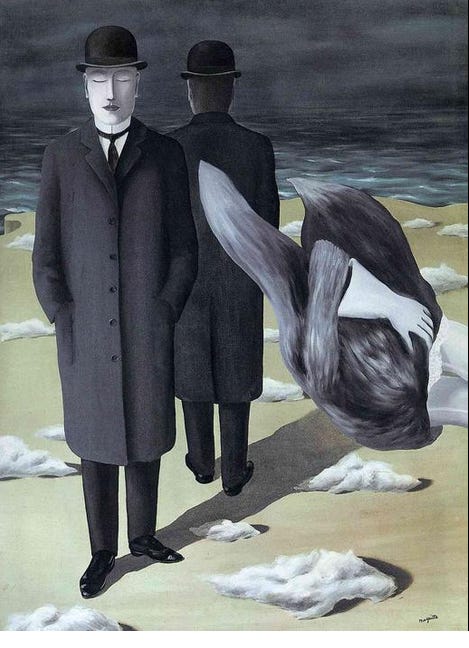

René Magritte - The Pilgrim

I can describe the Countess. Quite a long face and nose. Mole on the right cheek. Very pale. Hairdo of many ringlets. I can't describe the Amazon guy. The most recent delivery guy, what did he look like? Vaguely Asian? Kinda average height? If you were to show the portrait of Lady Susanna to her friends they'd say, yes, that's her. For some time, accuracy has been seen as an important, if not vital, element in portraiture. Portraits of the Queen (the real Queen not the new one) would often be fiercely criticised. Rubbish. Looks nothing like her. But let's just assume that the artist, John Michael Wright, captured not only her likeness but some sense of her presence.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, (nae kiddin’) Sophia Money-Coutts (nae, nae kiddin’) makes the following observation with regard to noted aesthete and intellectual, the Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer, MP.

“The Prime Minister prefers landscapes to “people staring down at him”, apparently. “When I was a lawyer, I used to have sort of pictures of judges. I don’t like it. I like landscapes.””

There you go, a wee dose of craving and aversion from the PM. Nobody wants a portrait of Margaret Thatcher staring at them while they’re being debriefed or, very likely, in any other circumstances. Portraits have some kind of presence.

Presence. I attribute “theory of mind” to the Amazon guy. Jeff Bezos may well have recruited and deployed an android army without letting anyone know but I'm inclined to believe that the Amazon guy is a human being and capable of thought and suffering. I can also very easily see what seems like evidence of thought in the portrait. She has information that I don’t have. She looks intelligent. The eyes are maybe a wee bit narrow in what might be scepticism, maybe a bit quizzical. Is she carrying out a careful and patient appraisal of the artist? She seems entirely at home in the fancy dress and pearls. It seems as if she's present. She's thirty years old. We don't question the frame when we look at a portrait nor do we question the concept of a snapshot. The artist has transcribed the likeness of Lady Susanna at a specific point in time. She looks out from a dark oval as if seen in a mirror or looking through a window from the past.

“From the far end of the corridor the mirror was watching us; and we discovered, with the inevitability of discoveries made late at night, that mirrors have something grotesque about them.”

Jorge Luis Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis, Tertius

So what's with the Amazon guy? The short answer is, that as a matter of direct experience, he is no more real than Susanna Hamilton. She can't talk but she does at least have a name. The Amazon guy is nameless and says very little if he speaks at all. The buzzer goes, he arises (in the lift), gives me the thing that I crave and then he passes away. He’s there for less than a minute. I very likely spent less than a minute in front of the portrait and, in stead of being present, open and receptive, I photographed it. I captured it with my phone to bear off as a prize rather than look at it. I was living, as Charlotte Joko Beck** puts it, a "potential life" rather than an actual one. I had the potential to look at the paintings but I wasn't fully engaged.

Portrait of Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo - Titian

National Portrait Gallery, London

“You talkin' to me? You talkin' to me? Then who the hell else are you talking... you talking to me? Well I'm the only one here.”

Travis Bickle - Taxi Driver

I was the only one there. Here’s the opportunity that I missed at the Portrait Gallery: When I leaned forward to look at the label beside the portrait of Lady Cassillis at some level, I was asking;

“Who is this?”

It could just as easily have been:

“What is this?”

Go a bit further and you might as well include when and where.

I was looking in the wrong direction.

René Magritte - The Meaning of Night

I could have asked the question of myself, as a koan - Who is this? - rather than directing my enquiry at the painting. I could have looked for the looker. The subject of a portrait is often shown making eye contact with the artist. Then the visitor to the gallery comes along and, in a genuinely amazing trick that nobody notices, the viewer occupies the space where the artist once was. So who is this? Not, who is Gerolamo? but who is Gerolamo (or Barbarigo) looking at? Any idea? This is not about art history - a very interesting subject - but suppose we just bin all the back story and all the biography and the historical context and the yah-di-yah-dah. If we stop caring about whether or not it’s Gerolamo or Barbarigo we could then ask Loch Kelly’s question:

“What is here now, when there’s no problem to solve? Who’s here?” **

Well?

"As most people know most of the cells within your skin are not your cells they are the cells either of parasites or of bacteria which, for the time being, are being helpful rather than parasitic, but can switch... And if you do that calculation the proportion of cells in your body which are human are equivalent to your left leg from the knee to the toe. That's the only human cells, all the rest are other cells, many of which are parasitic but not all."

Steve Jones

Emeritus Professor of Genetics at University College London

BBC Radio 4 - In Our Time: Parasitism

I’ve just measured my left leg from the knee to the toe. It’s about 86cm of leg and probably weighs, I don’t know, call it four kilos. If I were to saw that leg off I’m pretty sure I could get it in one of those of blue Ikea bags. Let’s say I saw it off and get it nicely in the Ikea bag. Damn. I forgot. I’ve got a taxi booked. That’s my cab just turned up. Will I look ridiculous, hopping along with blood dripping from the bag? Ach, it should be fine, I can hop in to the taxi and hop out at the other end. Nae bother. Cucumbersville, daddy-o, as a beatnik might put it. But possessed of an urgent need to see myself as others see me I hop to the front door where there’s a big mirror. But wait a minute… what was that about cells? Hold on… when I look in the mirror, who’s holding the bag?

* Douglas Harding, On Having no Head

** Waking Up, Charlotte Joko Beck, The Practice of Life, A Substitute Life

*** Waking Up, Loch Kelly, The Course of Awakening, No problem to Solve.